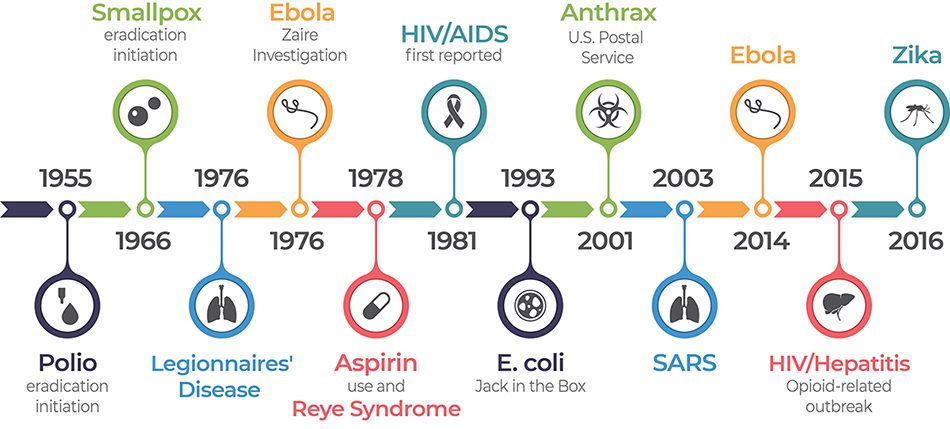

The industrialization of Europe which started in the 18th century produced urban slums which were swept periodically by epidemics of typhoid and typhus. In the 1830s, a cholera epidemic hit London. As the epidemic spread to Germany, Rudolf Virchow (1821– 1902) studied the obvious connection between poor sanitation and disease which became the genesis of the public health movement. The public health movement began in Germany in the 1840s.

While isolated geographically from the scourges of Europe, America was occasionally hit with epidemics of its own, especially in the growing east coast cities. Recognizing that disease may be coming from the ships that docked in their ports, cities instituted quarantines during outbreaks.

The history of public health has been a history of humanity’s battle with the disease and premature death. In what is frequently referred to as the old public health, our early efforts in disease prevention were directed at providing access to clean water, safe housing, and more nutritious and cleaner sources of food, especially meat products. We were also concerned with matters of personal hygiene well illustrated by our recent development of body and hand washing, town sewerage systems, quarantine laws, and population-based surveillance, screening, disinfection, and inoculation (Greene, 2001).

For modern industrialized societies, these measures led to higher rates of perinatal and maternal survival, decreases in infectious diseases, and increased life expectancy at all ages. After World War II, diseases of aging and affluence began to

occupy center stage of the public health agendas in these nations, although the problems of infectious diseases and poverty-related morbidity and mortality would continue to engage the health resources of developing countries. These long- standing patterns of morbidity and mortality would also still dog the health and welfare of marginal social groups in wealthy nations.

However, in the 1980s, helped along by new ideas about health promotion, public health filled out its vision of anti-disease public health with a complementary pro- health vision. Diseases such as circulatory illness (heart attacks, strokes, deep venous thrombosis, etc.) and cancers (especially of the bowel, skin, breast, or lung) became targets of new forms of surveillance, screening, and prevention.

In societies where the quality of water, employment, and housing were excellent, people were found to be overeating, overworking, and exposing themselves to high-risk substances such as tobacco, alcohol, asbestos, or UV radiation. Sedentary lifestyles had reduced fiber and increased fat in the diet and reduced exercise and fitness levels. International and workplace migration increased social and psychological stress as well as the desire for harmful forms of release. Suicide, automobile accidents, and drug-related deaths made sharp inroads into our patterns of morbidity.